Peps: The brain doesn’t really distinguish between intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. Norms and routines are useful longer-term change bets

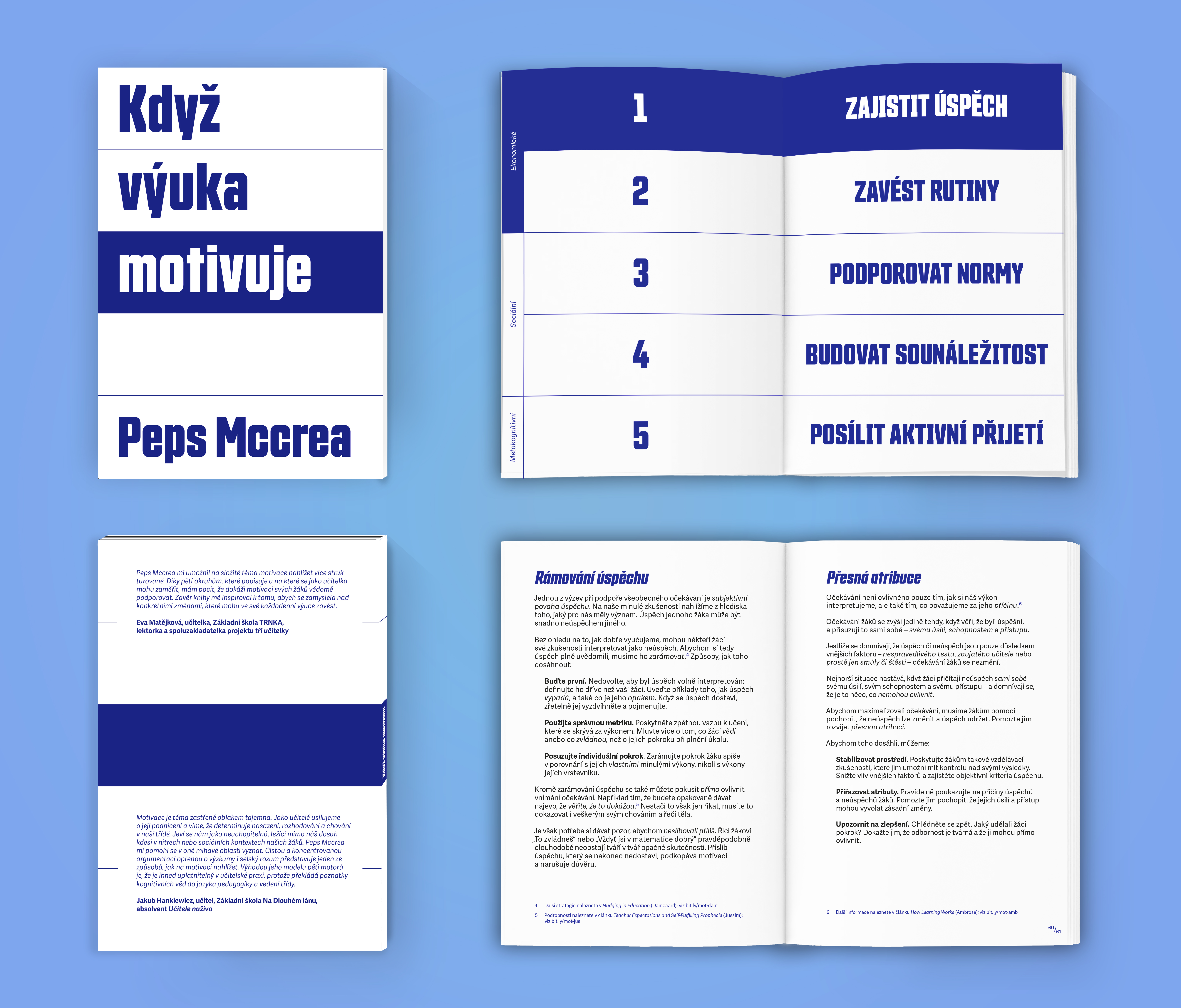

Peps Mccrea is an award-winning teacher educator, designer and author. He has been working on student motivation for a long time (and other topics are addressed eg. in his SNACKS). In January 2025 EDUkační LABoratoř published the Czech translation of Motivated Teaching, the first book in a four-part series. Is there such a thing as wrong motivation? And which, in turn, is the most effective? We asked Peps himself.

Peps Mccrea is Director of Education at Steplab and holds fellowship awards from the Young Academy and University of Brighton. Peps has three Masters degrees, two lovely kids, and multiple distracting tattoos (which he’ll tell you about over a beer). Visit pepsmccrea.com for the full shebang.

Your book, Motivated Teaching, is part of the High Impact Teaching series. In one of your interviews you said it had all started with a bet. Would you tell us more about all this?

Haha! Stephen Lockyer and I made a bet in around 2014 to see who could write the most books in a year. The plan was to try to write one a month… but it took me a decade to write 4! I think Stephen wrote a couple…

Most of us have heard about two kinds of motivation: extrinsic, or the bad one, and intrinsic, the good one. You say that the five drivers proposed in your book fall into the latter category. However, at least two of the drivers – routines or norms – may seem rather extrinsic. Can you explain that?

Yea, this is all quite murky tbh. Firstly, the brain doesn’t really distinguish between intrinsic and extrinsic: the same neural pathways are activated, and so the distinction is much more of a socially constructed thing than a hard science thing, and in reality: there is probably much more overlap that is reflected in the educational research literature. As in: what constitutes ‘intrinsic’ is probably more usefully thought about in terms of ‘how long the effect lasts’ rather than more traditional distinctions, and from this perspective, norms and routines are useful longer-term change bets, than say bribes or praise. Great question BTW (no-one else has ever pushed on this, but I think about it a lot)!

Teachers sometimes think that in order to motivate, instruction must be fun in the first place. Your book suggests it is rather irrelevant. Simultaneously, in his Teach Like a Champion, Doug Lemov writes about the joy of learning and how it is different from fun. Would you agree with him?

Yes, I’d say fun and joy are different. Have you heard of type 1 and type 2 fun? Type 1 is enjoyable in the moment, and type 2 is enjoyable on reflection or from a level up (eg. running a marathon is incredibly painful in the moment, but when you step back it is hugely joyful)… and I think education can definitely fall into the latter. Also: just becoming fluent in things can release dopamine. So good teaching will bring joy, bad teaching won’t (even thought it might be able to bring fun).

In about two years‘ time, Czech primary teachers will stop grading pupils in Year 1 and 2. Instead, they should write termly reports in all subjects. In your view, will such a step support pupils‘ genuine motivation to learn, instead of learning only for the sake of good grades? Could abandoning grades be the right choice for older pupils as well?

Gosh, this is a REALLY tricky one. My honest guess (which is probably wrong as there are few clear steers from the evidence for this kind of complex situation) is that it won’t really make much difference. Partly because there are many other things which will make a HUGELY greater difference (eg. amount of attention being paid in class, content of curriculum, ability to assess learning in valid ways).

Are there teachers or schools that have fully embraced the principles you recommend in your book? What impact have they seen on pupils’ learning and school culture?

So, there are many more teachers and schools who practice in ways that are aligned with the principles of my book these days. HOWEVER, it’s very hard to know whether it’s my book that has led them to this position or some other thing. It’s probably a combination of both. The schools which ARE strongly aligned are getting some pretty good results (both in terms of academic outcomes but also culture, character etc.). See: steplab.co/film for some examples.

You also write that „without a secure understanding of the key ideas and nuances, we risk developing ‘lethal’ mutations: practices that can do more harm than good“. Is it, hence, a risky business for a teacher to read your book and attempt to apply its principles to their teaching?

Haha! Yes, change is ALWAYS a risk. However, it’s much greater when we deal in superficial ideas. That’s why I spend a LOT of time trying to build the underlying ‘reasons and mechanics’ behind my suggestions, because this then reduces (but doesn’t eliminate completely) the risk of lethal mutations.

Is pupils‘ age linked to the efficiency of your five drivers? Should primary and secondary teachers read and apply the recommendations you make in a similar fashion, no matter how old their pupils are?

In general, our cognitive architecture is more similar than it is different. However, there are definitely some ways that it plays out differently for children at different stages. For example, belonging becomes a MUCH bigger deal when we hit adolescence, and norms are more powerful for younger children (just watch how they look and copy).

How applicable are your five drivers of motivation to children with ADHD or autism? Such pupils may find it hard to follow classroom routines or to obey school norms.

My understanding is that routines are even more important for students with special learning needs, as they provide a safe and predictable environment. The power of norms is mediated by feelings of belonging, and these children often feel a lack of belonging for various reasons, and that this is the area we should try to tackle first.

Teachers sometimes give up on some pupils, acknowledging their lack or even complete absence of motivation for a subject or an activity. Can such situations be avoided?

Yep. But only if we can get all the principles working in their favour. Not easy, or quick.

You warn that „promises of success that don’t eventually materialise will only serve to undermine motivation and erode trust“. Is there a sweet spot between the teacher’s genuine faith in a child’s success on one hand and, on the other, the concern that things may simply not work out the way we wish?

We can help pretty much every student learn way more than we think we can. Success is largely a technical problem, not a people problem.

Think of three particularly widespread and harmful myths about motivation. Now imagine you had the power to make them cease to exist. Which ones would you choose?

Lowering expectations is a form of kindness.

Motivated teaching is a minimalist yet dense text which can be read cover to cover within hours. While you make sure you navigate your reader towards grasping the book’s key concepts, the number of examples you give to support their understanding is very limited. Would you consider your book a suitable reading for students of teaching or novice teachers?

Good push. I preach about the power of examples in my books, but I do think there are ‘lethal mutation’ type risks associated with them (in this context anyways). And so, there’s a trade-off. Harry Fletcher-Wood writes books on similar topics, but with many more examples and so we could do an experiment to find out which is better!

Pavel Bobek & EDLB

READ SAMPLE (CZ) ▼